RESULTS ARE IN: Wooly Mammoth of ICC Named “Seymour” After Instagram Poll

Meet Seymour! A relatively unknown wooly mammoth found on campus in the 1970’s was finally given a name after waiting more than 18,000 years.

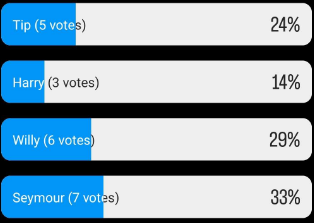

This was decided through a poll on our Instagram, @iccharbinger, where the name “Seymour” beat “Willy” by only one vote and “Tip” by two, despite there being 21 total voters. The name Harry came last behind with only 3 votes.

The remains, which can be found in a geology classroom on the East Peoria campus, include a chunk of its tusk, several giant teeth, and some bone fragments found when the horticulture building was under construction. “One of the construction workers noticed the fragments of the tusk coming out of the ground,” says Ed Stermer, an ICC geology professor.

“We had one of our science professors at the time, Ed Tarbuck and Fred Lutyens who taught here and they said “Hey, can you just pause construction for a bit? Let’s try to remove this, it’s pretty cool.’”

The biggest part of the wooly mammoth found is its tusk. Based on it, we can know a lot about this particular mammoth.

First of all, it is part of a much larger tusk. “That mammoth tusk could be up to six feet long. So this is just a very, very small part of what was probably a very long and curved tusk,” says Stermer.

We also know the mammoth is a “he”, due to the width of the tusk being 14.5 centimeters.

“Mammoth tusks from males had diameters measuring well above 10 centimeters and—in the largest males—up to 20 centimeters in diameter. Tusks from fully-grown female mammoths consistently measure less than nine centimeters across,” said former ICC professor Tom Griffins in his 2014 Peoria Magazine feature article about the tusk.

There were also two teeth found with the tusk. Because of this, we can determine its age as well.

“The ICC mammoth had molars of a size and shape that would have first appeared in a 45-to-50-year-old mammoth—the final set of molar teeth he would have had. However, the teeth are only moderately worn down. Thus, we can be quite sure that he was about 50 years old when he died,” said Griffins in his article.

Because they are moderately worn down, we know he “certainly did not starve to death because of worn-down teeth or an inability to chew,” Griffins said.

But what do we know about the mammoth’s death?

We know it probably died alone, which is quite common in male elephants.

“In elephants, males tend to get kicked out at an early age and they live alone. So this poor guy was probably wandering alone,” says Stermer.

However, Stermer says recent research shows that this wooly mammoth may not have been alone his whole life after exile.

“The older males find the younger ones, pass on their knowledge, and then they go their separate ways,” he says.

This was discovered because of a site dubbed “The Mammoth Site” in the Black Hills of South Dakota, where an all-male group of more than 60 wooly mammoths were found preserved in a sinkhole.

We also know that the ICC wooly mammoth is one of the southernmost mammoth fossils found in North America.

“There was about a quarter-mile-thick sheet of ice that came down from Canada and stopped right here,” says Stermer.

In fact, it is only 300 miles from the record holder for the southernmost mammoth remains, which were found in Golconda, Illinois.

The last mammoths died in North America about 17,000 years ago, meaning this was one of the last wooly mammoths to live in the region.

Climate change probably killed them off. “As the ice began to retreat, the world was getting warmer. We went from a cold Tundra environment to a much warmer environment with trees,” says Stermer. Mammoths may not have been able to digest the vegetation of this new climate.

“The mammoths either migrated to a more favorable environment or they couldn’t sustain themselves around here and just passed away,” says Stermer.

Overall, however, wooly mammoth species was driven extinct by being “overkilled, overgrilled, and underchilled,” says Professor Cheryl Resnick, a geology professor at ICC. This means humans killed them off in some areas and climate change in others. However, in Illinois at least, it was probably climate change, as humans probably were not in the region at the time.

While the ICC wooly mammoth is certainly impressive, findings of wooly mammoths are not too uncommon. In fact, everyday people find them all the time.

Ed Tarbuck, the former ICC professor who helped excavate the ICC wooly mammoth, “would go around to local bars sometimes, and a couple of times there were tusks on the wall. He would offer to buy them,” says Resnick.

“One of the teeth in the geology exhibit was brought by a student. He was out hiking around a ravine near his backyard weathering out,” she says.

If you would like to see the remains the student found or the wooly mammoth remains found on campus, they can both be viewed in Room 313E.

If you would like to know more about wooly mammoths and other prehistoric creatures in the area, one of the best places is the Field Museum in Chicago and the Illinois State Museum in Springfield.

They have a replica of a mammoth and a giant sloth, both of which lived around the same time in Illinois.